Michael & Janet Created The Black Rock Star

In an article by Rolling Stone, collaborators of Michael and Janet Jackson reflect on how ‘Beat It’ and ‘Black Cat’ crossed genre and racial boundaries and changed pop forever!

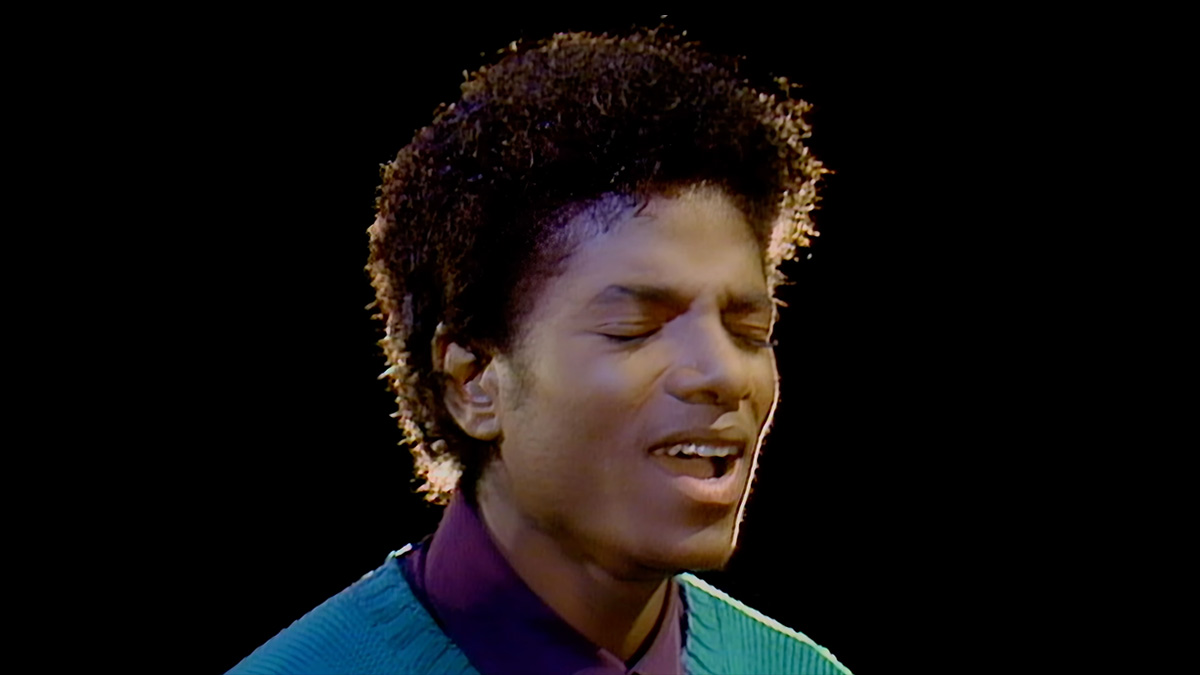

In 1982, Michael Jackson wasn’t yet Michael Jackson, megastar. Before ‘Thriller,’ the then–24-year-old had released five solo albums but was still defining his own sound separate from the success of the Jackson 5. He had won his first Grammy for ‘Off the Wall,’ and begun a long and fruitful relationship with producer Quincy Jones. But he needed a boundary-breaking showstopper that could help make him a household name. For Michael to forge an alliance with a beloved hard-rock guitar heavyweight on future smash ‘Beat It’ was a major coup.

“Eddie Van Halen was much more beloved in the MTV world than Michael Jackson,” critic Greg Tate reflects. “He was a bigger star than Michael Jackson.”

For what would become one of Jackson’s biggest hits, the pop star and Jones made one of the finest and shrewdest, creative calls of their joint career: adding Van Halen and his instantly recognizable finger-tapping guitar-work to ‘Beat It.’

While ‘Thriller’ was already a hit with the world, the release of the single, which paired Jackson’s steely R&B vocals with a glitzy hair-metal edge, helped solidify it as the biggest album of all time.

“I wanted to write the type of rock song that I would go out and buy,” Jackson said of the song. “But also something totally different from the rock music I was hearing on Top 40 radio.”

He achieved both. The success of ‘Thriller’ was an obvious breakthrough for Jackson, but it also signified a tectonic shift for black artists and the loosening boundaries of pop music. MTV began playing the historic videos for ‘Billie Jean’ and ‘Beat It,’ helping to make it the youth hub of the Eighties and paving the way for more representation for black artists just before the explosion of hip-hop.

By that time, rock had become inseparable from whiteness; the explosion of subgenres like punk and heavy metal had pulled rock further away from its roots in black music. Disco was a brief solace, a genre that saw both rock and pop heavyweights (including Jackson) exploring it in an effort to stay on top. With a song like ‘Beat It,’ one that owed as much to metal as it did to R&B, Jackson made room for the image of a new kind of black rock star, distinct from founding fathers like Chuck Berry and newly relevant for the Eighties.

Guitarist Steve Stevens would work with Jackson on his following album, ‘Bad,’ delivering a blistering solo on ‘Dirty Diana.’ It was another key hard-rock moment for Jackson, and certainly not his last.

“Credit, really in the case of myself and Eddie Van Halen, (goes) to Ted Templeman, Van Halen’s producer and my A&R guy when I was signed to Warner Brothers,” Stevens reminisces to Rolling Stone. At the time, Stevens was making a name for himself as Billy Idol’s guitarist. “Ted was friends with Quincy Jones, so when it came time after the success of ‘Beat It,’ the story that I got was Quincy called Ted and said ‘OK, who is the hot new rock guitar player? We have another rock track on the ‘Bad’ record.’ And Ted suggested that Quincy call me.”

In the studio for a session that didn’t last much longer than three hours, Stevens met Jackson the Artist, as opposed to an entourage-laden megastar. Jackson and Jones let Stevens do what he wanted on the track’s heavy solo, offering only a bit of guidance in terms of vision. It wasn’t until they filmed the video that the guitarist got a sense of how much Jackson had become invested in rock.

“He was preparing for his first major tour and up until that time, he had only toured with the Jackson 5,” Stevens explains. “He was adamant that he wanted a big arena-rock production, so he started asking me what sound company we use and what lighting company.”

They even began exchanging music recommendations. “One of the funniest things he asked: ‘Hey, do you know Mötley Crüe?'” He quotes with a chuckle. “He also did a spot-on impression of David Lee Roth for me. Now, if you could imagine how surreal that is, Michael Jackson doing David Lee Roth.”

Months later, Stevens joined Jackson to perform ‘Dirty Diana’ at Madison Square Garden for an NAACP benefit and was able to witness firsthand the results of Jackson’s meticulous tour planning. “When I saw it, it was like a rock show,” he recalls. “The staging, lighting, everything was on that level, and I immediately thought ‘Yeah, he gets it.’ He wanted to appear big and larger than life.”

Jennifer Batten, Jackson’s touring guitarist, was in the thick of his rock-inspired show for three tours as well as the star’s landmark 1993 Super Bowl halftime performance. Prior to her time with Jackson, Batten played everything from folk to funk. In the early Eighties, she lived in San Diego and worked with a cover band. They were in rehearsal when she first heard ‘Beat It’ on the radio.

“I’ll never forget it,” she tells Rolling Stone. “Everybody’s jaws just dropped when the solo hit because it was so unusual and exotic for a pop tune. Usually, solos for pop tunes are very predictable and this was wild as hell.”

Afterwards, she set out to memorize Van Halen’s solo and “failed three times” because of all the new techniques. “Eventually I nailed it, and boy did that pay off!”

Batten spent two months in rehearsals with Jackson and the singers, band and dancers for the ‘Bad’ tour. It was a “playground” for Jackson, according to the guitarist. The leather and metal of his attire at the time translated to the larger-than-life production, one if its era’s most tech-savvy and advanced tours. Batten remembers Jackson as a voracious listener with his finger on the pulse.

“He listened to every kind of music, from classical to showtunes to metal,” she explains. “Metal has a certain power to it that Jackson was certainly intrigued with. I’m sure he also had marketing in mind when he linked up with Van Halen. It was an obvious crossover that brought him to an audience he wouldn’t have gotten without that.”

Just as hip-hop was “black America’s CNN,” as Chuck D so incisively put it, hard rock, specifically heavy metal, had become the primary outlet for white male rage. So for Jackson, the squeaky-clean baby brother of the Jackson 5 whose most suggestive song prior to ‘Thriller’ was the saccharine disco hit ‘Don’t Stop Till You Get Enough,’ the fusion which began with ‘Beat It’ and continued with ‘Dirty Diana’ was a major risk. At the time, mainstream black rockers were scarce; Prince’s breakthrough ‘1999’ would arrive around the same time as ‘Thriller’ but he wouldn’t realize his heavier rock potential until 1984’s ‘Purple Rain.’

Even though ‘Beat It’ had paved the way, a similar musical move from Jackson’s younger sister came as its own unique shock. In August 1990, Janet Jackson released ‘Black Cat,’ the sixth single off her politically charged fourth solo album ‘Rhythm Nation 1814.’ In the Eighties, she had struggled and ultimately succeeded in breaking free from her older brother’s superstardom; she was a pop princess who became a queen with the trailblazing ‘Control.’ She reaffirmed her power with ‘Rhythm Nation’ and would spend the Nineties and early 2000s experimenting with R&B and her own image.

Source: Rolling Stone & MJWN

Est. 1998

Est. 1998