Billboard ‘Xscape’ Article

A little less than a year ago, L.A. Reid met John Branca for dinner at Cecconi’s in West Hollywood. Reid had been the chairman and CEO of Epic Records (“the house that Thriller built,” as Reid calls it) since July 2011, and he’d inherited a cold label that so far hadn’t gotten much hotter.

Branca had resumed his role as Michael Jackson’s adviser and lawyer shortly before Jackson’s death in 2009, and during his time as co-executor of the Jackson estate had erased the estate’s $500 million debt, thanks to the This Is It concert film (which grossed $261 million worldwide), and lucrative Jackson performance properties with Cirque du Soleil.

One of the items on the table that night was Reid’s idea for a Jackson biopic covering his life between the age of 19 — when he filmed The Wiz, and first worked with Quincy Jones — and 24, when he and Jones reshaped the world with Thriller.

Branca had simple answer for Reid: No.

“John said to me, ‘That’s wonderful. Why? Why should we allow you to do that?’ ” Reid, 57, remembers today. Branca complained that during his time at Epic, Reid had done nothing for Jackson. Reid’s first two years at the label had coincided with his tenure as a judge on The X Factor on Fox (a decision he now calls “horrible”), and Branca seized on this too. “He said, ‘You don’t talk about Michael when you’re on TV,’ ” says Reid. “He starts to berate me. I walked right into it.”

But Reid saw a chance to prove himself, and so asked for something else, something bigger: to go into the vaults and hear the recordings that Jackson — who was known to work on as many as 70 songs for each album — had left behind. “Let me hear everything,” he said to Branca. “And then let me go out and put my team together and make an album on Michael.”

“I was just being a lying-ass record man,” says Reid. “Because I had no idea what was in the vaults.” But he says this now with a smile, and the confidence that comes with pursuing an unorthodox strategy and creating something no one believed possible — an album that deserves to be discussed in the context of the remarkable music that Jackson made from Off the Wall in 1979 to Invincible in 2001.

“Xscape,” which comes out May 13, is eight tracks of Jackson vocals set to new music from Timbaland and J-Roc, Rodney Jerkins, Stargate and John McClain, the former A&M Records executive who is co-executor of the Jackson estate with Branca. The originals they worked with were recorded from 1983 to 1999, the period just after Thriller to just before Invincible.

The finished songs are not remixes. Reid chose a riskier path, charging each of his producers to create what are essentially new songs based only on Jackson’s vocal tracks. Timbaland — the project’s executive producer, who oversaw five tracks with his collaborator J-Roc — talks about it almost like a ghost story, Jackson’s disembodied voice urging him on, dissuading him from sounds that weren’t innovative enough, and giving his blessing when they were.

This is the second full album in a deal between the Jackson estate and Sony Music to put out previously unreleased material, reportedly worth $250 million. The first, 2010’s Michael, focused on the most recent material Jackson was recording in the years leading up to his death. It was completed by a half dozen producers, many from the original sessions, who tried to carry out his intentions as best they could. The results fell well short of Jackson’s studio perfectionism. Branca calls the process “somewhat chaotic” and notes it lacked an overall guiding vision.

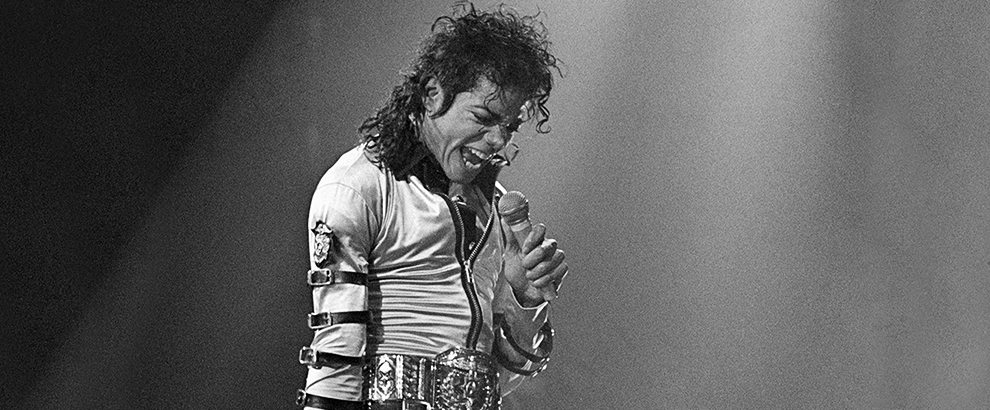

In the time since its release, Michael has posted sales of 540,000 — by no means overwhelming. Still, Jackson remains, five years after his death, big business. Last year, Michael Jackson: The Immortal World Tour, a partnership between the Jackson estate and Cirque du Soleil, became the ninth-top-grossing tour of all time, passing The Rolling Stones’ Voodoo Lounge tour in 1994 and 1995 with earnings of $325.1 million from 407 shows that drew almost 3 million concertgoers. Immortal is back on tour in North America, and a second Cirque du Soleil show, One, began a residency at Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas in May 2013.

Jackson’s albums have sold 12.8 million in the United States since his death, according to Nielsen SoundScan — 8 million of those in the months immediately following his June 25, 2009 death, making him the best-selling artist of that year. Since then, Jackson’s sales have slowed. Last year, his albums moved 584,000, less than Elvis Presley (1.1 million) and Johnny Cash (969,000), but more than Whitney Houston (310,000) and Jimi Hendrix (539,000). “Xscape” will provide a lift, though how much of one is unclear.

As welcome as a hit record would be, Reid and all involved also see a higher purpose: To reanimate Jackson’s presence in today’s pop universe. There is no question his influence lives on. Listen to the songs on the Billboard Hot 100 most weeks and you’ll hear tracks by Jackson disciples — right now it’s Pharrell Williams, who has long chased what he calls Jackson’s “stutter pop” sound, at No. 1 with “Happy” and Justin Timberlake at No. 9 with “Not a Bad Thing” — co-produced by part of the “Xscape” team, Timbaland and J-Roc. In working on the album, Timbaland says he asked himself, “How would I hear this on the radio against Katy Perry? Would it sound old, would it sound new? [I] had to make sure that it can compete with everything that is going on today in the pop world.”

In April, Reid gathered with the producers who worked on “Xscape,” save McClain, to talk with Billboard about the making of the album, and to shoot a documentary. They met at Henson Studios in Hollywood, the former A&M Studios on La Brea, built in 1966 on the site of Charlie Chaplin’s studio. Jones and Jackson recorded “We Are the World” here in Studio A, and Jackson — who obsessively screened footage of Chaplin as a form of study — was known to rehearse on the soundstage.

Some of these men had known and worked with Jackson — Jerkins, 36, a hitmaker for Brandy and Destiny’s Child, first met Jackson at 16, and began work with him at 19. “He asked me for a year,” says Jerkins of Jackson. It turned out to be more like three, from 1999 to 2001. Reid himself produced one of the source tracks on “Xscape,” “Slave to the Rhythm,” with his partner Kenneth “Babyface” Edmunds in 1989 (and almost signed Jackson in 2005 when he was chairman/CEO of Island Def Jam). It has been refashioned for “Xscape” by Timbaland. “He asked [Rodney] to work with him for a year,” jokes Reid. “This shows you where I’m at as a producer — he asked me for two weeks.”

Jackson had wanted to work with the Norwegian production duo Stargate — Mikkel Eriksen and Tor Hermansen, both 41 — known for their hits with Rihanna and Perry. The singer was a fan of their songs for Ne-Yo, and he met with them at the Midtown Manhattan Chinese restaurant Mr. K’s to discuss future projects. “Just the two of us, and managers, and Blanket was there as well,” says Eriksen. “Down in the basement.”

“Did he eat?” asks Reid.

“He ate — he brought his own chopsticks,” says Hermansen.

As for Timbaland, 42, Reid felt his consistent innovation was in tune with Jackson’s desire to always carve out a unique sound. As Jackson did, Timbaland acts out the sounds in his head, beatboxing and vocalizing in the studio. And like Jackson, he’s relentless in his search for new approaches. “I always felt like I was ahead of the times and nobody understood my method of music. I feel like everything around us is music. That’s why I use crickets in songs and birds and spoons and door knobs or a car motor, and I just make it a rhythm.”

Timbaland was Reid’s first call. “I said, ‘I want to come into the studio. I don’t want to talk over the telephone,’ ” remembers Reid. The two met at Jungle Studios on West 27th Street in Manhattan, built and owned by Alicia Keys. “Like normal, the studio control room was full of people — musicians, sound engineers, assistants, friends, songwriters — a lot of people in the room,” says Reid. “I didn’t want to talk about it in a group setting. So I said, ‘Tim, can we talk?’ We walked out and I’m whispering into his ear, like it’s this big special project. I said, ‘Listen to this: “Michael Jackson produced by Timbaland.” ‘ ”

“I felt like he was giving me a task,” says Timbaland. “Like, ‘Let me see how good you really are. How about Michael Jackson?'”

For Reid himself, the project is also a chance to show how good he really is. “When I came to Epic Records I didn’t know exactly why,” he says. Since he co-founded LaFace Records with Edmunds 25 years ago, Reid has ascended to the top spots at both Arista and Island Def Jam, overseeing breakthrough records from TLC, Usher, Outkast, Pink, Avril Lavigne and Rihanna. “Did I really need another job at another record company?” he asks. And though Epic is on the upswing, thanks to recent hits from Future, Kongos and A Great Big World, his first 18 months there were rocky. “Until we started working on the Michael Jackson project … I didn’t get it, you know?” he says. “I needed to sink my teeth into something that had the potential of being great.”

The process began with the Jackson estate going through the recording archives, stored in the multiple warehouses of Jackson’s belongings — everything from his wardrobe, jewelry and cars to his memos and writings — in Southern California. “We’ve computerized much of it,” says Branca of the recordings. “We’ve indexed and logged it so we have ready access to things.”

There is no shortage of material. In his prime, Jackson worked relentlessly. He’d use multiple studios, so he could move from song to song, sometimes for 16 to 18 hours at a stretch. He sang rather than played, but could sing chords or arrangements for his team, and brought them demos of voice orchestrations (with beatboxed rhythms) constructed in his home studio. “He has an entire record in his head and tries to make people deliver it to him,” songwriter-producer-engineer Bill Bottrell told Joseph Vogel, author of Man in the Music (and the liner notes for “Xscape”). “His job is to extract from musicians and producers and engineers what he hears when he wakes up in the morning.”

Jackson over-recorded for every project, working on songs for years, and sometimes returning to them for later albums — “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’ ” began during the Off the Wall sessions but ended up on Thriller. He kept pushing himself and those around him. When he was collaborating with Jerkins on “Xscape,” which was recorded between 1999 and 2001, he sent the producer out to junkyards with a DAT recorder to find new percussion sounds. “[I’d] start hitting stuff and was like, ‘Wow, that could fit in a song. That could go with the kick.’ After awhile, the sounds started coming to life, and it was all of those moments of him constantly challenging for that next thing. He was so into trying to figure out how to create sounds.

“‘Where is the sound that is going to make you listen to it over and over again?’ ” he’d ask Jerkins. “We have to be pioneers and create that next sound.”

From all this material, Reid and longtime Sony A&R man John Doelp had a clear target. They wanted to find songs, says Reid, that “Michael sang beginning to end multiple times, multiple tracks, because that was the only indication that I could find that spoke to Michael’s love to the songs.” Reid knew this well — when he and Edmunds recorded the original “Slave to the Rhythm” with Jackson in Los Angeles in 1989, during the Dangerous sessions, Jackson recorded the vocal 24 times.

“And it was not once and fix the bad note,” says Reid. “No, he sang the song from top to bottom 24 times without a bathroom break, without a water break, without a ‘Give me a moment.’ He would sing the song and say, ‘OK, give me another track, I can do it better,’ and he’d do it again. ‘I can nail this. Give me another track,’ and he’d do it again. Each time he’s getting better and better, but by the time you got to track 13, 14 we got lost, because it all started to sound the same. At that point he’d perfected it, but he just kept going.”

Going into the vaults, Branca and Karen Langford — who knows what’s in the archive warehouses as well as anyone — selected 24 possibilities that met Reid and Doelp’s specifications. They in turn narrowed the field to 20, which were edited down to about 14. Eight will be on “Xscape,” though several more were prepared (a deluxe edition will also feature the original tracks). The choices are not exactly surprises, though the omissions may be. The tracks that Jackson cut with Queen’s Freddie Mercury in 1983 are not on “Xscape,” although both Brian May and Roger Taylor of Queen spoke about working on them last year. And though a version of “Slave to the Rhythm” featuring Justin Bieber leaked last August (supported by a series of Bieber tweets), you won’t hear it on “Xscape.”

Hardcore Jackson fans will recognize almost all of these tracks. Most were in some form of completion, and have leaked through the years, in part or whole. Some of the leaks can still be heard online. That doesn’t mean, though, that “Xscape”‘s producers had heard them. Timbaland and Stargate’s Eriksen both began by listening to the source material that Reid presented, and both quickly decided to forgo the instrumental tracks and work with only Jackson’s vocals and a few stray noises picked up by the microphone.

“You can hear his foot in the booth when he’s singing, and his fingers snapping,” says Jerkins. “It was all raw, it was real. It wasn’t like, ‘Take the snaps out, take the stomps out.’ No — it’s real. It’s him in the booth, and he’s feeling what he’s doing.”

“As a producer, he makes our job easy,” says Hermansen. “All the stuff that’s on the vocal track, it’d makes you want to get up and dance.”

For Eriksen and Hermansen, the project brought them back to their early days, remixing late-’90s American R&B hits — Mary J. Blige, Mariah Carey, Brandy — for the European market, layering in new instrumental tracks behind a cappella vocals. But what was a pleasure for them was more complicated for Timbaland.

“There was moments where I broke down,” he says. “It was very hard to do. I’m like, ‘I’m doing Michael Jackson but I can’t talk to him. So how do I channel him?’ ” When he and J-Roc were in the studio reworking “Loving You” — a song written and produced by Jackson at his home studio at the Encino, Calif., house he lived in before Neverland — the first version they came up with was terrible. “I was like, ‘I don’t think Mike would like this. We got to go back. We got to simplify it,’ ” he says. As they did — going for a rich sound he says feels like “Boyz II Men meets today” — he heard Jackson’s voice saying, “That’s it, Tim.”I’d look around, and nobody be in the room,” he says. “I never shared this story, even with my co-producer, Jerome. He like, ‘You all right?’ I’m like, ‘Nah, I’m cool, man. I’m just …’ And I’m sitting and I’m like, ‘Yo, I just heard something. I know I ain’t crazy. I know what I heard.’ So it’s like his spirit resonated through me to give me the OK.”

The focus on Jackson’s a cappella vocals became a guiding principle for “Xscape.” The new versions put him front and center (“he’s louder,” says Reid). “We actually took out quite a few things just to let Michael breathe,” says Hermansen. “Michael is singing and he’s sounding great — just let him breathe and let him do his thing.”

For Reid, this project is personal on several levels. Born in 1956, two years before Jackson, he grew up with Jackson’s music, first seeing The Jackson 5 at the Ohio State Fair. “I’m a kid, and Michael’s a kid, and I was just blown away by him,” he says. “When little Michael Jackson opened his mouth, his voiced soared through the concert ground.”

Reid remembers his first meeting with Jackson, at a BMI event in Los Angeles. “I took a picture with him,” he says. “I had a whole head of hair full of really wet jerry curl, juice running all down my neck.” It wasn’t so long after that Jackson flew Reid and Edmunds to Neverland to talk about working together. They arrived by helicopter, signed a non-disclosure (“because that’s how it was when you visited Michael”) and waited in a library for Jackson.

“We’re there for maybe five minutes but I’m thinking it felt more like 20 — anticipation, nervousness, keeping my eye on the door, waiting for Michael to come in, Michael’s coming. He never comes through that door. He comes from a secret door — the books move and in walks Michael.” The three started talking about music, about what they loved right then. Jackson mentioned “The Knowledge,” a song on his sister Janet’s album Rhythm Nation 1814, produced by Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis. Reid began to get worried. “Every song he named was written and produced by Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis. So I’m looking at Kenny like, ‘I think Michael has the wrong guys. I think he wanted Jimmy Jam and Terry.’ ”

But soon enough Jackson was naming songs from Edmunds’ Tender Lover, then dominating the R&B and pop charts. The day ended with a screening in Jackson’s movie theater (“there was an attendant there in full uniform with a little cap, like we were in the 1940s”), where they watched a 1983 video of Jackson and Prince onstage with James Brown, followed by a screening of Prince’s 1986 movie, Under the Cherry Moon.

When they began to work together, Jackson picked out a demo, just drums and bass, and said, “That’s the one. Finish it.” But the track, “Slave to the Rhythm,” wasn’t really finished until “Xscape.”

As he progressed to running labels, Reid kept in touch with Jackson, and talked about signing him to Island Def Jam. “He called me Mr. President,” says Reid. “It was the sweetest thing in the world.” The two met at the Dorchester Hotel in London. “He said, ‘I don’t want another hit, I don’t want to just make another record. I want to do something great. If it can’t be great, if it can’t be groundbreaking, if it can’t be massive, if you’re not as committed as I am, then we shouldn’t do it. But if you commit to me I promise I’ll commit to you.” It wasn’t to be. Jackson signed a short-lived deal with Sheik Abdulla bin Hamad Al Khalifa, the prince of Bahrain.

“Michael and I parted ways knowing that we wanted to work together,” says Reid. “Xscape” fulfills that intention. It is as focused and coherent as any posthumous album could be, expressing the creative liberties that Jackson sought in his music. Built from the ground up around Jackson’s voice and legacy, it succeeds simply by sounding like Michael Jackson music, full of joy and desperation, often with no distinction between the two. And it transports the spirit of the late pop genius from the past into the future, the place Jackson always wanted his music to live.”

This article first appeared in Billboard Magazine and you are able to purchase it here.

Source: Billboard & MJWN

Song of the week

Est. 1998

Est. 1998